Script, Code, Information

How to Differentiate Analogies in the 'Prehistory' of Molecular Biology

(überarb. und übersetzte Version von "Schrift und das 'Rätsel des Lebendigen", Kogge 2010)

In: History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences 34 (2012), S. 595-626.

Abstract

It is widely assumed that the use of semiotic terminology in molecular biology (e.g. code, information, transcription) originates from the specific historical circumstances at the time of the introduction of the sign-like vocabulary. This paper challenges that assumption, arguing that the use of such vocabulary was not only motivated by external factors, but is deeply rooted in the way biological and genetic questions were conceptualized between 1870 and 1950. Tracing the discussions of leading biologists, the paper analyzes semiotic analogies by distinguishing between three different layers: (1) Notational and scriptural vocabulary, (2) the introduction of the concept of the code, and (3) the paradigm of information technology. While the second and third layer indeed seem to be motivated by external circumstances, the paper shows that the use of notational and scriptural vocabulary is closely tied to biological inquiries and phenomena. Gene-centrism, with its problematic deterministic implications, stems from the later superimpositions, and not – as commonly alleged – from the usage of semiotic terms in general. The paper claims that the scriptural vocabulary to this day offers perspectives that can help to bring to light the subtleties in the connections between heredity and ontogenesis.

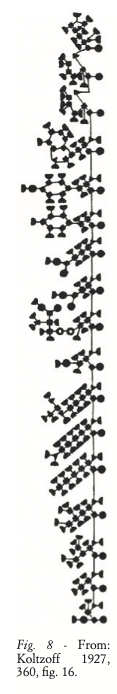

„This chain structure of eighteen elements allowed for a much more complex recombination than what seemed possible in Weismann’s work: “The number of possible isomers during the intramolecular repositioning of the 18 amino acids is very large, approximately one quintillion” (Koltzoff 1927, 361). […]

By invoking such an unimaginable number of combinatorial possibilities, Koltzoff pursues two goals […] Secondly, it becomes evident that chromosomes remain constant in their original order during cell division, because “the probability of all the separated parts coming together anew in their previous order is not higher than the probability of all the disassembled letter blocks for a print sheet positioning themselves on their own and by coincidence in their previous order” (Koltzoff 1927, 367f ).

Koltzoff’s choice of an analogy between molecular and scriptural structures obviously arises from certain properties that are also characteristic of writing: a lasting, linear arrangement of distinct elements, whose exact order is constitutive and is therefore replicated in identical patterns.“

Leseprobe

The conceptual system of molecular biology rests upon a large number of semiotic concepts such as “letter”, “transcription”, “reading”, “code”, “information”, “message”, and “translation”. The resulting terminology – with phrases such as “open reading frame”, “transcription assay”, “editing”, “translational read-through”, “high throughput library screen”, “sequence motifs”, or “cDNA encoding proteins” – cannot be attributed merely to the purposes of popularization, as has been observed for the case of the “draft” of a genome (Bostanci 2010). Rather, it is constitutive in the sense that today the terms are “all implemented into powerful technologies” (Rheinberger 2001, 124).[1]

On the other hand, the past few decades have seen the formation of a discourse criticizing the deployment of semiotic vocabulary in molecular biology, from the skeptical reflections of scientific actors in the 1960s and 1970s,[2] via Susan Oyama’s The Ontogeny of Information of 1985, to the extensive studies and controversies that have marked the debates of the past ten years.[3]

Some of the criticisms of molecular biology’s semiotic terminology have been formulated as an objection to the terms’ metaphoricity. We read, for example, that the concept of information in molecular biology is “little more than a metaphor that masquerades as a theoretical concept” (Sarkar 1996, 187).[4] Other authors do not criticize the use of metaphorical language as such, considering it unavoidable, but the problematic effects and blind spots that are caused by specificmetaphors. Thus, for example, it is the result of “powerful metaphors of information and programs” that the “discourse of gene action … lent the cytoplasm scientific invisibility” (Keller 1995, 24). Crucial to many of these criticisms is the argument that molecular biology’s semiotic terminology implies a gene-centered and deterministic view that does not do justice to the complexity of cellular processes. This is the claim made, for example, by Lily Kay when she argues that the “information discourse” rests on a notion of the genetic code as “the site of life’s command and control” that was born in the historical situation of World War II and the Cold War, whereas today the aim must be “to loosen the grip of genetic determinism” (Kay 2000, 5, XIX).

The present paper aims to take further the idea that it is particular metaphors which imply problematic effects and invisibilities. I argue that the confrontation between advocates and opponents of semiotic terminology in molecular biology can be defused to a considerable extent: a reconstruction of different discursive and research traditions between 1870 and 1950 shows that the development of semiotic concepts – and in particular scriptural concepts – was historically antecedent to, and systematically independent of, the communication-technology concepts of code and information. And although the philosophy and history of science have delivered convincing arguments that the terms “code” and “information”, derived from the technical transmission of information, are closely associated with a hierarchical, deterministic logic, the same does not apply to scriptural vocabulary: script-based terms were initially only expressions of a particular image of the biology of heredity that arose out of the confluence of different research traditions, an image that was – and is – by no means necessarily gene-centered or deterministic.[5]

In this paper, the distinction between scriptural vocabulary and the vocabulary of communication technology is established by means of a historical presentation. I show that in the emergence of molecular biology, semiotic and scriptural concepts did not arise only with the rise of discourses of communication technology and cybernetics, but earlier and in close connection with specific biological studies and phenomena.

If I address different genetic, biochemical, and biophysical discourses under the label of a “prehistory” of molecular biology, this is not to presuppose a teleology of development that is somehow inevitable. Rather, I assume a notion of stabilization in the history of science, basing myself on what Ian Hacking, following Andrew Pickering, called “robust fit”. “Robust fit” refers to a stabilization in the relationship between “theory, phenomenology, schematic model, and apparatus”, arising out of the “dialectic of resistance and accommodation” in the experimental process (Hacking 1999, 72). A stabilization of this kind comes about through a large number of correlations and corroborations, but it is not predetermined: the course of research might have taken a different route and molded different, stable patterns.[6]Although the “prehistory” of molecular biology is not a single, continuous experimental system, this does not preclude us from regarding the conceptual system of molecular biology as it was elaborated by, in particular, Francis Crick in the early 1950s as the product of a stabilization of different discourses, practices, and technologies.

The “robust fit” approach implies a second important point. In this way of thinking, it becomes immediately plausible that conceptual innovations may occur on different levels: the spectrum reaches from interventions that are close to the research and the phenomenon, to those on the level of general “theoretical models” and “speculative conjectures” (Hacking 1999, 71). The central claim of my historical reconstruction is therefore as follows: the scriptural concepts that emerged between 1870 and 1950 not only linguistically, but also pictorially and technologically, prove to be analogies that were delineated within the research process and close to the phenomenon, whereas the concepts of code and information should be viewed as terminological loans on the level of general theory. Regarding the status of the metaphors, then, a distinction can be drawn between the scriptural concepts that took shape as catalysts and products in the course of a process of stabilization in research, and the superimposition onto them of the concepts of code and information, a superimposition that would probably have been impossible without the historical situation of World War II and the Cold War.

[1] John Maynard-Smith succinctly expressed the cardinal function of semiotic concepts in molecular biology when he drew a close parallel between the genetic code and human communication (“The signals are symbolic, just as words are”, Maynard-Smith 2000b, 217) and noted “that in describing molecular proofreading, I found it hard to avoid using the words ‘rule’ and ‘correct’” (Maynard-Smith 2000a, [1]78).

[2] As early as 1963, Erwin Chargaff observed mockingly (if with less than complete historical accuracy) that between 1937 and 1944 “the concept of ‘biological information’ raised its head and began to sport a multicolored beard which has become ever more luxurious despite numerous applications of Occam’s razor” (Chargaff 1963, 163).

[3] The most important works to be noted in this context are Refiguring Life: Metaphors of Twentieth-Century Biology (1995) and The Century of the Gene (2000) by Evelyn Fox Keller and Who wrote the Book of Life: A History of the Genetic Code by Lily Kay (2000); of the philosophical debates, most relevant is the one that arose in the wake of John Maynard-Smith’s The Concept of Information in Biology, documented in Philosophy of Science 67 (2000). On more recent debates, see Griffiths 2001; Nehrlich, Hellsten 2004; Jablonka, Lamb 2005; Rosenberg 2006; Stotz 2006; Stotz, Botanci, Griffiths 2006; García-Sancho 2006, Ŝustar 2007; Stegmann 2009; Bergstrom and Rosvall 2009; Godfrey-Smith 2008; Chow-White, García-Sancho 2011.

[4] Similar views can be found in Janich 1999 and Mahner, Bunge 2000.

[5] The talk of script and text tends to valorize the role of cellular processes as against that of DNA, as can be seen, for example, when one of the best-known cell biology textbooks uses the analogy with scriptural concepts to show that the shape of the living being cannot be derived from the “DNA text”: “a complete description of the DNA sequence of an organism … would no more enable us to reconstruct the organism than a list of English words in a dictionary would enable us to reconstruct a play by Shakespeare.” Alberts et al. 2004, 267.

[6] On the relationship between robust fit and contingency in the development of science, see also Trizio 2008.